Oriana Fallaci is of course the famous European atheist that took common Cause with the Catholic Church. It was not always a easy relationship. She was blunt to say the least.She was quite clear she thought John Paul the II was naive about the Muslim threat.

At the big Communion and LIberation Conference one of the big crowded speeches were those relating to her.

The Ratiznger Forum on this page of the thread has several good posts about her and the speakers that talked about her.All translated, I am posting two of these in full

They include

4,000 flock to hear about

Oriana Fallaci

By ALESSANDRA STOPPA

which appeared in the Italian Paper Libero

They describe her as terrible. Arrogant. Alone and sometimes enragingly unpleasant. Her friendship was as tempestuous as a stormy sky. But they say it lovingly. Three men declare their love for a woman who was consumed by a thirst for freedom.

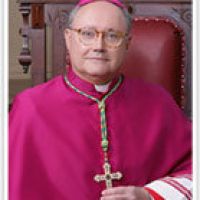

Two of them were among her dearest and rare friends. One held her hand before she died. The other still sees her in his dreams and hears her call him during sleepless nights. They are Mons. Rino Fisichella, rector of the Pontifical Lateran University, and Vittorio Feltri, editor of Libero, who paid homage to Oriana Fallaci on the second day of the Meeting of Comunione e Liberazione in Rimini. Before an overflow audience, many of them having to watch on maxi-screens, standing or squatting on the floor. Four thousand people turned up to listen to a theologian bishop and a journalist from Bergamo talk about their mutual friend.

Moderated by a third friend of Oriana, the journalist Renato Farina, who has just written a book called Maestri di umanita [Masters of humanity], with a chapter devoted to Fallaci. Farina said that the motto of this 28th annual Meeting in Rimini, "The truth is the destiny for which we were created" made him think about her - it evokes for him "the face and the voice" of Oriana Fallaci. Feltri said the lady "never succeeded to have a lasting relationship." But he talks about her as about someone who is not seated with him at the same table but is nevertheless present.

As insistently and impetutously present as when "she roused Europe." By simply writing to Europe with her articles and books. Most notably, when she conceived that 'formidable little book' to a 'baby never born'. When she defended every last comma of her articles as much as she did the sacredness of life. "Without ever being sentimental," Feltri said, "she tore to pieces all the arguments of the pro-abortion people with sheer reason." And for this, she became isolated, abandoned.

There followed crisis years over Vietnam. She believed that basically, the Americans were right. So every word from her was greeted by assaults from the predominantly Marxist intelligentsia of the time. But she was never daunted by the propsect of standing alone.

Feltri met her in 1989. His impression: "She always insisted she was right, and most of the time she was." But she yelled, she did not hesitate to call others foolish, and when she swore, she used 'true and Tuscan' swear words. They were on the telephone for hours every night. "The phone would ring when I had just stuck my fork into my pasta, but I would drop anything for these nightly talks." And he was never able to feel any anger against her, "even when one day she came to give me a fur coat." "A fur coat for me?"

But he still keeps it. As he still keeps a measure of jealousy that he felt about the late-stage friendship between Oriana and Fisichella. "I was jealous, because she often spoke about him. About the 'monsignore' with whom she never quarrelled." "That's right," said Fisichella. "She never let herself go with me. No swear words, no impetuousness.

Although we spoke of everything - most of it I can only keep in my heart." The last things she ever wrote were letters to her theologian friend - when even her eyes wer already affected by the ten cancers that were eating her up. He read some passages from it, and to him, it's like listening to her. She writes that she feels 'less alone' when she reads his books and those of Ratzinger. She writes about her profound admiration for the man who is now Pope and whom she succeeded to meet finally. "It is a desire I have had for some time," she wrote Fisichella. "I wouild like to see him, but very privately." Then she worries about clerical etiquette which she has always detested, adn she dedicates one letter expressing her despair "because if they require ceremonial clothes, it will be a problem...I only have spartan men's jackets..."

Moreover, "I will never never again cover my head" if veils should be required. She had worn one to see the Ayatollah Khomeini, then she took it off in his presence. She survived that! Fisichella remembers her 'cigarette binges'. She smoked like the devil, and he was always ready with candles to absorb the smell and the smoke. "She developed affections for people, but she remained alone. She closed herself up in her apartment in New York to think of the mystery hovering over her, of the death she was facing." [Towards the end, she decided to go home to Italy, to die in a hospital in Florence.]

They disputed the first chapter of Genesis, she hated Adam and Eve, "but then I explained it to her, and she changed her mind, as she could." She always started off like one of the Furies but then she would calm down. She screamed how much she detested priests 'as much as the anarchists of Lugano hate them" but then she ended up seeking him out, wrote to him, and if anyone dared to 'touch' her Christian West, she defended it as the dearest thing to her and to the world. Farina points out she had 'few friends, but great ones' like those who spoke about her at the Meeting, and with both she spoke about God.

Feltri told her he thought "there canot be a Master Planner who does everything out of love and then allows all the carnage with which the world has always been full," that he at least could not believe that, and she told him, "You are right = I never thought of it that way." She thought about death a lot. At the end, she asked Fisichella to be sure to hold her hand when it came. "If you are right (about God), then hold my hand." She did not believe in God - "Perhaps she only wanted to be a littke like God," Feltri remarked. But even if she did not believe,`"not even at night, when one's ideas can be different,", she "always lived within Christianity".

From when she was a child. She would say, "My grandfather was a socialist but he was a believer. And my mother always went to Mass." They all spoke to her about Christianity. And 'she defended it all her life, with all her being, before a threat which she thought was clear to all from where it was coming," Feltri said. She asked him, to "continue the fight, even when I am no longer around, you must continue." Perhaps that is why he still dreams about her. "I don't believe in the hereafter," he says, "and yet I hear her call me, 'Vittorio...'

Today when he gets ready to go to bed, he looks behind and below - "One never knows - she may be back." She was alone, but 'provided company to others." Especially 'to her children', as she called her books. Farina said "she was so proud of them". She would curse because she had to repeat so often that she was an atheist. But then, she said she wanted to die looking at Brunelleschi's dome which crowns the cathedral of Florence. And listening to it cathedral bells. Fisichella had them peal for her on the day of her funeral. "One could well say she was an atheist, but at the same time, one who harbored within her a nostalgia for God."

and of Course the American Reporter John Allen has a great piece

The deathbed friendship between a bishop and an atheist

All Things Catholic

by John L. Allen, Jr. Friday, Aug. 24, 2007

Conventional wisdom has it, "There are no atheists in foxholes." In truth, atheists can be found even in foxholes, but often they're atheists whose deepest yearning is to be wrong.

In just that spirit, among people who believe that Western civilization today is locked in mortal combat with radical Islam, there's a growing contingent of what we might call "Christian atheists," meaning non-believers nonetheless committed to a strong defense of Christian culture.

In this quirky galaxy, no star burned brighter than that of the provocative Italian writer Oriana Fallaci until her death in September 2006. Fallaci's credentials as a non-believer were never in doubt. She once defined Christianity as "a beautiful fable," and wrote: "I'm tired of having to repeat, in writing and also orally, that I'm an atheist. In addition to being a secularist, I'm also profoundly anti-clerical. Priests don't sit well with me, just as they didn't with the anarchists of Lugano." (That's a reference to a city on the Swiss-Italian border where 19th century anarchists were chased out because of their opposition to the ultra-Catholic Hapsburg Empire.)

Many conservative Christians nonetheless regard Fallaci as a hero, a veneration clearly on display Tuesday in Rimini, Italy, where the annual "Meeting" sponsored by the Catholic movement Communion and Liberation ends tomorrow. One of the most popular sessions was devoted to Fallaci, and it featured the man whom she asked to be at her side as she died: Bishop Rino Fisichella, rector of the Lateran University in Rome, and an intimate of Pope Benedict XVI.

Their improbable friendship illustrates an important current percolating in contemporary Western culture, a budding détente between institutional Christianity and some of its sharpest Enlightenment-inspired critics, motivated by a deep sense of shared peril. In part on the strength of her mega-best seller La rabbia e l'orgoglio (The Rage and the Pride), Fallaci became the leading voice of Western protest against militant Islam. Together with British writer Bat Ye'or, she popularized the term "Eurabia" to describe what she saw as a creeping Islamicization of Europe, transforming the continent from the cradle of Christian civilization into an outpost of the Arab world.

A colleague of Fallaci and a fellow non-believer, Italian journalist Vittorio Feltri, summed up their position during the Tuesday panel: "All of us have been shaped by a Christian culture. Facing a threat from the outside, and we all know where it comes from, we have to rally around our culture, which is the culture of Christianity, even if in the end we can't bring ourselves to believe in God, except perhaps, every now and then, at night. This was Fallaci's argument, and I share it from the first word to the very last."

A degree of affinity between Fallaci and the cultural positions of the Catholic church actually predates today's frisson over Islam. In the 1970s, during a bitter referendum campaign in Italy which eventually legalized abortion, Fallaci wrote her famous work Lettera a un bambino non mai nato (Letter to a Child Never Born). She had found herself pregnant, decided to keep the child, and then lost it. The book is regarded by some as one of the most eloquent reflections on maternity and the gift of life ever written, and it brought Fallaci to the attention of a new German bishop and fellow intellectual, Joseph Ratzinger.

In late August 2005, Pope Benedict XVI met with Fallaci at his summer residence at Castel Gandolfo, granting what was in effect her dying wish, since by that stage Fallaci was already debilitated by the cancer that killed her a year later. On Tuesday, Fisichella recounted the story of his friendship with Fallaci, which began in the final years of her life after she wrote a letter praising an interview he had given on Islam and religious freedom to the Italian paper Corriere della Sera. Towards the end, Fisichella said, the two would talk on the phone sometimes three or four times a day. (Fallaci was in New York, where she had lived for decades, undergoing treatment at the Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.) Fisichella said that despite Fallaci's atheism and anti-clericalism, he saw signs of vestigial Christianity.

Fallaci returned to Italy in her final days because, she said, she didn't want to die in exile. She asked Fisichella to help arrange a room for her in Florence where she could look out at the famous dome of Brunelleschi atop the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. She also requested a CD with the sound of church bells to play softly in the background. It was Fallaci's desire, Fisichella said, that on the day of her funeral, the bells of the cathedral would ring out.

It wasn't easy to arrange, Fisichella said. Though he didn't elaborate, it's well known that some Catholics objected to bestowing such an honor upon a professed atheist, while others argued that it would be seen as an endorsement of her stridently anti-Islamic views. Nonetheless, Fisichella said, he managed to pull it off. "With a great deal of difficulty, due to various polemics, it happened that when her coffin left the clinic to go to the cemetery, the bells of the Cathedral of Florence pealed for Oriana Fallaci," he said, to thunderous applause from the crowd in Rimini.

It's worth quoting Fisichella at length about his final experiences with Fallaci. "I held her hand the day before she died, as I had promised, a hand by then reduced to just skin and bones. I also gave her a blessing. I did so consciously, because Oriana Fallaci was baptized. She was a Christian. I did it because Oriana Fallaci made her first Communion, because she was confirmed. I did it because many times Oriana Fallaci told me how, with her father, taught to do so by her father, she read the Bible of Douay. She knew all the illustrations of her Douay Bible, which she decided to leave to me. I did so because many times during the last weeks of her life, when it was just the two of us by her bed and she was suffering enormously, she would look at me, raise her eyes to Heaven, and say, 'If you exist, why don't you let me live?' She didn't say, 'Don't make me suffer,' but rather, 'Let me live.' I did it because Oriana Fallaci loved life, and because the God of Christians is the God of life. I did it because, even though Oriana Fallaci said that she didn't believe, she had great hope. "During those days, a phrase came into my mind from the posthumously published book of Ignazio Silone called Severina.

The protagonist is a sister who had left the convent, who is now dying from a wound she received during a protest. At a certain point, one of the sisters from the convent comes to her deathbed and takes her hand, saying, 'Severina, Severina, tell me that you believe!' Severina looks at her and says, 'No, but I hope.' I believe we Christians have a great responsibility to talk about our faith with the language of hope.

Quite often, people won't understand us when we talk about the content of our faith. But without doubt, people of today can understand when we talk about hope, if we talk about the mystery of our existence and the meaning of our lives … "I held Oriana Fallaci's hand as a priest, as a bishop, asking the Lord to look upon her with great mercy, if for no other reason than that she suffered so greatly, because she was so alone, and because in her last years, radically and with deep conviction, she defended the idea that this country belongs to the West. She defended like few others the profoundly Christian roots of the civilization to which we all belong, including the faith that, let's not forget, God forever offers to us as a great gift. We have to remember this woman for what she did, for what she said and wrote.

She was a great woman, a great Italian, who deserves to be viewed with respect, and who now belongs to the history books." Fisichella drew a sustained standing ovation. Whatever one makes of Fallaci's views on Islam or anything else, this deathbed friendship between a bishop and an atheist is a remarkable story. Among other things, it illustrates a perverse but seemingly ironclad law of human life: Sometimes the perception of a common threat can dissolve differences and open hearts to a degree that otherwise would have been difficult to imagine.

By all accounts, Fallaci was an earthquake of a human being. She was a perfectionist when it came to her work, Feltri said, often agonizing long into the night over single commas. She could also erupt at her closest friends and colleagues, and was never one to shrink from a fight, even with people she otherwise admired.

An occasional target of her scorn was Pope John Paul II, whom she regarded as naïve and weak regarding the Islamic threat. Once, when John Paul had devoted an Angelus address to urging hospitality for Muslim immigrants in Europe, Fallaci shot back acerbically: "Your Holiness, why don't you take them into the Vatican? On the condition, of course, that they don't smear the Sistine Chapel with shit ..." During the Rimini session, Italian journalist Renato Farina revealed another, more personal reason why Fallaci had a beef with the late pope.

When Lettera a un bambino non mai nato appeared in the 1970s, it was an enormous worldwide success. Among the many places it was reprinted was the weekly newspaper of the Archdiocese of Krakow, Poland, led by then-Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, who would become John Paul II. When Fallaci wrote to the archdiocese to request payment, Wojtyla told his secretary, Fr. Stanislaw Dziwisz, who is today himself the Cardinal of Krakow, to write back informing Fallaci that because Poland was a Communist country it wasn't customary to pay copyright fees.

"After that, she decided Wojtyla was a bad guy," Farina laughed. "A great figure, but a bad guy." * * * For those readers who can follow spoken Italian, a video of the session on Fallaci from Rimini is available on-line at mediacenter.corriere.it/MediaCenter/action/player?uuid=16b9109e-50cb-11dc-8a4a-0003...

Saturday, August 25, 2007

If you are a Oriana Fallaci fan read this

Posted by

James H

at

8/25/2007 04:46:00 PM

![]()

Labels: Catholic, Islam, Pope Benedict, vatican

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

The video is not so good, it is a little delayed. You can download the complete audio at: radioradicale.it

Just look for Rimini.

Great translations!

Thanks

Post a Comment